|

New Public Management in Japan and Southeast Asian Countries: A Magic Sword for Governance Reform?Osamu Koike, PhD., June 21, 2000 Paper presented at the IIAS/Japan Joint Panel on Public Administration, SummaryAt the turn of the century, administrative reforms become a fad not only in advanced countries but also in developing countries. In western democracies a prevailing theme of administrative reform in the 1980s was a "small government," backed by a dubious theory of "new conservatism." In the 1990s a driving reform idea was slightly transformed to what is called "reinventing government" (Osborne and Gaebler 1992). Not only bashing the bureaucrats, "new liberal" leaders advocated the reform of the government that "works better and costs less" (Gore 1993). These leaders welcomed managing tools from the private sector making the government more accountable for results. In some countries, such as the United Kingdom, New Zealand, and Australia, reforms take on a more radical manner like privatization, market testing, contracting out, adopting the theories of public choice and a "quasi-market." In the end, all these efforts are now covered under the name of "New Public Management (NPM)." In developing nations, administrative reforms have also become crucial for political leaders. Democratic forces have criticized a tyrannical "developmental state," once applauded for its contribution to economic growth. In addition, international aid organizations request developing countries to modernize their governance for effective use of development assistance. Quite interestingly, proposed measures for "good governance" contain some ideas of NPM such as "accountability" or "decentralization," which appears to be less easy to adapt even for the advanced countries. It is clear that New Public Management is somewhat effective for governance reform both in developed and developing countries. However, it is difficult, or appears to be meaningless in some cases, to impose some measures of NPM to a country without taking into consideration the political environment. As for the Asian Pacific countries, in order to make NPM work, we would be more successful promoting the exchange of information of public management through various channels. Theoretical Ambiguity of the NPMNPM is not an established theory but seems like a salad bowl of different ideas for government reform. It will be able to sort through two broad categories. The first approach attempts to change government structure from the centralized, hierarchical bureaucracies to become decentralized small units that will be more customer-friendly. Reform prescriptions include: market testing, contracting-out, splitting of the planning core organization and implementing agency, external evaluation of the agency performance, etc. These measures have been thought out from the theories of "neo classical economics" and "new institutional economics." Theorists assume that people can regulate a "wasteful" bureau of government by putting them into competition with the private sector, or into the "quasi-market" (Ferlie et.al. 1996). The second approach relates to the organizational change of the public sector. It challenges the traditional Weberian theory of public administration. This approach originates from business management improvements since the 1980s. Two best selling books, "In Search of Excellence" (Peters and Waterman, Jr. 1982) and "Reengineering the Corporation" (Hammer and Champy 1993), have influenced public managers to adopt business success stories into their organizations. "Breaking through Bureaucracy" (Barzelay 1992) and "Reinventing Government" " (Osborne and Gaebler 1992) are the most influential books both for federal and local government managers in the U.S. Reform measures includes the TQM, "reengineering," flatten organization, program evaluation, performance pay, bench marking, Management by Objectives, etc. In summary, NPM includes many approaches, ranging from structural reform to the improvement of an accounting system. Therefore, it becomes a catchy word for the world political leaders. However, we should note that NPM is neither a first-aid kit nor a "magic sword" for government reform. It contains different, even conflicting values. When we attempt to adopt some measures of NPM, we should distinguish which is adoptable and valuable to our government and which is not. New Public Management in JapanJapan has had a tradition of a "strong state" since the Meiji Era (Silverman 1993). Though Japan transformed from the old regime to a democratic one following the World War II, strong bureaucracies had survived to lead the recovery of the national economy. In the 1970s, the U.S. and European countries criticized that the Japanese market had been unfairly closed to foreign capital. In 1981 the Government established the Provisional Commission for Administrative Reform to "reconstruct government finance without tax increases" and to prepare for the age of "globalization." The PACR, chaired by Mr. Toshio Doko, who was a famous business leader, proposed the overhauling of government and recommended the promotion of deregulation, decentralization, and privatization (Wright and Sakurai 1987). In 1985, the deficit-ridden Japanese National Railways was privatized into seven independent companies despite strong opposition from labor unions. Public opinion supported the idea of a business-like government. However, during the days the "cozy triangles" - politicians, bureaucrats, and business groups - were strong enough to ignore recommendations of the Reform Commission (Koike 1995). In the late 1990s, a reform-minded Prime Minister Hashimoto Ryutaro established the "Administrative Reform Council" and he became the chairman of the Council. The Council adopted ideas of New Public Management and proposed the following measures:

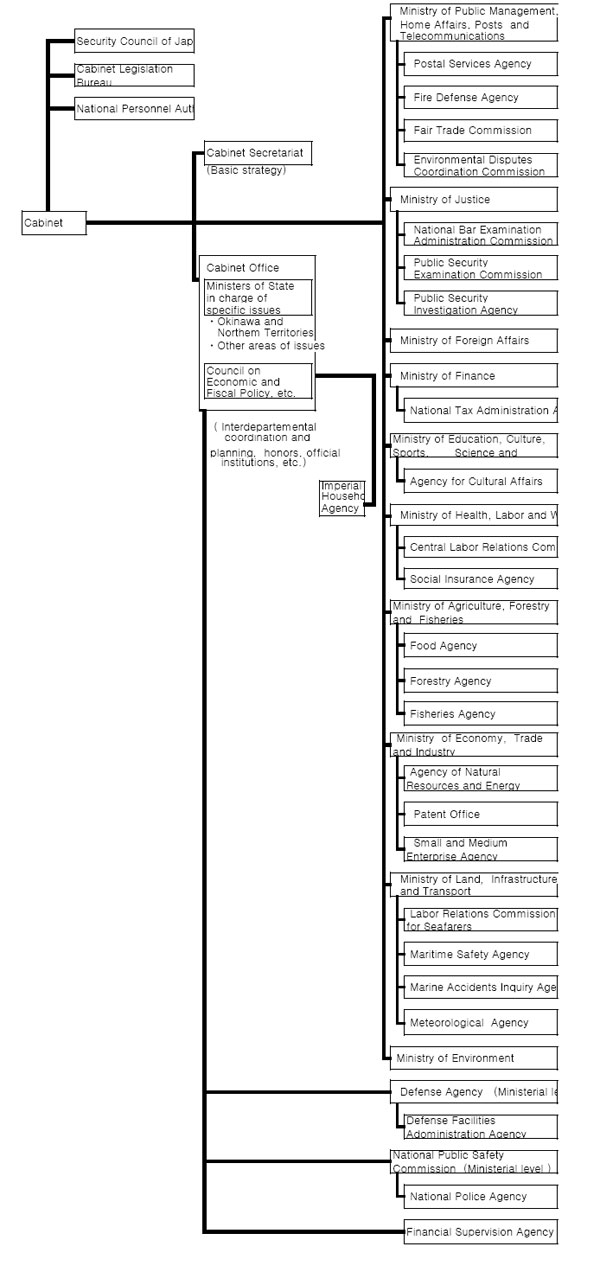

Creation of the Cabinet OfficeThe new Cabinet Office is a staff organization for the Prime Minister. It coordinates governmental policies under the direction of the Prime Minister. Some agencies and independent organs (the Defense Agency, the Finance Agency, the National Safety Commission, etc.) are transferred to the Cabinet Office. The law to establish the Cabinet Office passed the Diet in July 1999. Reorganization of central ministries and agenciesReorganization of the central body of the government was the highest priority of Hashimoto Administration. Under the direction of the Prime Minister, the Reform Council prepared a plan to reduce the number of central ministries and agencies by half. Reduction will be achieved mainly through the annexation of ministries and agencies. In addition, the government has set a date to privatize the Ministry of Post and Telecommunication by 2003. In July 1999, the Reorganization Act passed the Diet. The new organizations of the central Government, which start in January 2001, are shown in Appendix A. Deputy MinisterTo strengthen political leadership over the ministries, the government introduced deputy-ministers in each Cabinet ministry to assist the minister in place of the existing parliamentary vice-minister. A total of 22 deputy-ministers will be assigned to each Cabinet ministry. In addition, the government created 26 "parliamentary aides" who deal with specific policy-making and planning under the direction of the minister. It means that nearly 50 political appointees plus 14 ministers (the Ministers of the State) will come into the administration (Koike 1999). Independent administrative corporationThe government has transferred 80 government agencies to the Independent Administrative Corporation (IAC). The list includes mint, printing, national hospitals, national museums, and labs. In the IAC, an agency head prepares a mid-term performance plan and manages the budget provided by the government. The status of the employees is divided into the two categories: public officials and non-public officials. The primary purpose of IAC is "to separate policy-making functions and policy-implementing functions and to improve the efficiency and quality of services for the people by granting more autonomy and responsibilities to corporations and also to ensure the transparency of the operation (Kaneko 1999)." The most controversial issue at present is a transfer of national universities to IAC. DecentralizationBased on the recommendations of the Decentralization Promotion Committee, the government revised related laws to decentralize national authority and to allow more local autonomy. First, the Agency Delegation Function System, which legitimized overall control of local governments by the central government, was abolished. It will transform center and local governments from a commander-obedience relationship to be more equal in footing. Second, it established third-party organs to solve intergovernmental conflict. However, centralized intergovernmental fiscal relations have not changed and this issue awaits further discussion (Koike and Wright 1998). Civil Service ReformIn March 1999, the Civil Service System Deliberation Council submitted a report to reform the national civil service system. The Council proposed reform agendas as follows: the revision of the entrance examination system; introduction of merit pay principle; establishment of ethics; extension of retirement; promotion of personal exchanges between the public and private sectors, and so on. The items sound healthy; however, it is undeniable that the recommendations are increment and essentially Christmas tree-like. Apparent through recent administrative reform, Japanese leaders seem to be positive towards adopting NPM measures. However, it seems less evident that political leaders really understand the meaning of a "customer-driven" or "result- oriented" government. For instance, the creation of giant ministries seems to be distant from the idea of NPM that stresses to strengthen accountability of public organization by the decentralization. In the case of independent administrative corporations, expecting results of service improvement are unquestioned, while the government emphasizes the downsizing of the central administrative machinery. We may say that it is in a transitional period from a traditional bureaucratic state to the customer-oriented governance, however, the future prospect of Japan's administrative reform remains uncertain. Administrative Reforms in ASEAN CountriesSince the decolonization in the 1950s, underdeveloped countries had moved toward the stronger governments to assist in the development of their nations. In Southeast Asia, political leaders tended to depend much on bureaucracies to tailor and enforce the national development plans. In the process of development, major industries were nationalized in these countries. However, productivity of nationalized industry tended to be secondary, where the political leaders utilized government corporations for employment of political supporters. After the oil crises in the 1970s, foreign companies rushed to Asia seeking to lower production costs. As a result, Southeast Asian countries achieved a high economic growth. This has been called the "Asian miracle" (Flynn 1999). However, the more the countries developed, the more people demanded democracy. As shown in the recent political changes in Philippines, Indonesia and Malaysia, the old-styled authoritative regimes have allowed more democracy and local autonomy. Further, the government reform imperatives come from the out side. Since the 1990s, international aid organizations like the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) request recipient countries to improve governance for the effective use of development assistance, providing fund and experts for civil service reform and improvement of public management. In Southeast Asian countries, demand for government reform became more serious after the crash of financial markets in 1997. Agendas for government reform in the developing countries range from the establishment of fundamentals for governance to modernization as in the developed countries. Reform strategies will include followings:

A serious problem is that they have to pursue conflicting values at the same time. To establish a credible government, for example, it is necessary for leaders to disclose government information to the public. However, governments tend to hide information that might be advantageous to opposing forces. In pursuing value in efficiency through privatizing state corporations, political leaders tend to prefer them to remain inefficient due to fears of mass unemployment. As for the problems of an efficient government, many countries take measures for anti-corruption, TQM, and the civil service reform. However, governing parties are often less supportive of civil service reform especially when they utilize political appointment to control bureaucracies. In particular, decentralization and citizen participation seem difficult where local ethnic groups demand local autonomy. For leaders such reforms appear to reduce the centripetal force of the central government over the periphery. Finally, we can say that it will be difficult and even risky to adopt the New Public Management to the administrative reform in developing countries, unless taking steps for establishing fundamentals of modern governance. It is common for political leaders to rush to the catchy copies of reform tools. Rather, they should invest more in the "capacity-building" of the state through the establishment of a fair political system and solid legal foundations, and through the human resource development (Grindle 1997). Transnational cooperation for governance reformAs mentioned above, NPM is not a magic sword. Rather, it will be effective when it is customized for each political environment. Prior to the customization, we should establish a new operating system for governance based on the principle of fairness, accountability, credibility, and efficiency. For that purpose, it is rational to promote information exchange on governance reform among the developed and developing states. For instance, Japan's experience of privatizing public corporations would be a lesson for the states that propose deficit-ridden state corporations. Further, positive use of transnational bodies seems very effective. Not only the International Institute of Administrative Sciences and IASIA, but also the utilization of regional organizations for the study of public management, would be effective. In addition, personnel exchanges of management experts among the countries will contribute to the development of public management. In Japan, the Japanese International Cooperation Agency (JICA) conducts a variety of training programs for public officials from the developing countries. Yokohama National University launched a new "Legal Studies and Development Scholarship Program" for the students from those countries in the process of economic transition. The objective of the scholarship program is "to train individuals who will be in a position to assist in the smooth implementation of solid legal foundations appropriate to market economies." We believe such transnational cooperation will contribute to the progress of public management in this region. References

Contact: Osamu Koike, Ph.D. Do not quote without author's permission

Appendix ANational Government in 2001  |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

| Copyright 2005 - The Asia Pacific Panel on Public Administration |